Python Language OOP Attributes and Properties: Difference between revisions

| (99 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

=Overview= | =Overview= | ||

Attributes are variables associated with a class that | [[#Attribute|Attributes]] are variables associated with a class that carry state either for the class itself, or for the instances of that class. They are other Python objects stored "inside" the object. | ||

[[#Property|Properties]] are class constructs that behave like attributes, but are not variables. Technically, bona-fide attributes, properties and also the methods are all attributes on a class. [[Python_Language_OOP#Methods|Methods]] are just callable attributes. For a discussion on how to decide between attributes and properties, see [[#When_to_Use_Attributes_and_When_to_Use_Properties|When to Use Attributes and When to Use Properties]]. | |||

=When to Use Attributes and When to Use Properties= | |||

= | |||

Always use a standard attribute until you need to control access to it in some way. The only difference between an attribute and a property is that we can invoke custom actions automatically when a property is retrieved, set or deleted. | |||

Properties are useful when the values need to be cached. The first time the value is retrieved, the lookup and the calculation is performed. Then, the value can be cached locally, so the next time the value is requested, we return the stored data. | |||

Custom getters are also useful for attributes that need to be calculated on the fly, based on other object attributes. | |||

Custom setters are useful for validation. They can be used to proxy a value to another location. | |||

=Attributes= | |||

An object | Attributes are variables associated with a class that hold state either for the instances of that class ([[#Instance_Attribute|instance attributes]]) or for the class itself ([[#Class_Attribute|class attributes]]). An object instance carries its state as attributes. To differentiate attributes from [[#Property|properties]], they are sometimes referred to as '''standard data attributes'''. | ||

==<span id='Instance_Attribute'></span>Instance Attributes== | |||

===Declaring Instance Attributes=== | |||

All instance attributes must be declared inside the <code>[[Python_Language_OOP#init_.28.29|__init__()]]</code> method. | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | |||

class A: | |||

def __init__(self): | |||

self.color = 'blue' | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

If an attribute is first used in a method other than <code>__init__()</code>, static analysis identifies this as a warning "instance attribute defined outside __init__()". | |||

The attributes can be accessed inside the class definition using <code>self.<attribute-name></code>. Outside the class definition, they can be accessed via the variable holding the reference to the class instance: <code>my_instance.<attribute-name></code> | ===Accessing and Mutating Instance Attributes=== | ||

Idiomatic Python favors direct attribute access. The instance attributes can be accessed and mutated inside the class definition using <code>self.<attribute-name></code>. Outside the class definition, they can be accessed and mutated via the variable holding the reference to the class instance: <code>my_instance.<attribute-name></code>. If an attribute was not explicitly declared inside the instance with <code>self.some_attribute</code>, even just to be assigned to <code>None</code>, an attempt to access the attribute will end up in: | |||

<font size=-1> | <font size=-1> | ||

AttributeError: 'MyClass' object has no attribute 'some_attribute' | AttributeError: 'MyClass' object has no attribute 'some_attribute' | ||

</font> | </font> | ||

=== | ===Deleting Instance Attributes=== | ||

Prepending a single underscore (_) | An attribute can also be deleted, meaning that it will be removed from the instance it was deleted from. | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | |||

class A: | |||

def __init__(self): | |||

self.color = 'blue' | |||

def delete_attr(self): | |||

del self.color | |||

a = A() | |||

a2 = A() | |||

a2.delete_attr() | |||

print(a.color) # this will display "blue" | |||

print(a2.color) # this will raise AttributeError: 'A' object has no attribute 'color' | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

Deleting instance attributes has limited usefulness. | |||

===<span id='Naming_Convention'></span>Attribute Visibility=== | |||

Unlike in other languages, all attributes are public in Python. There are '''naming conventions''' to designate attributes as protected, or even private, but these conventions depend on others' willingness to abide by them - the interpreter won't prevent access to an attribute conventionally declared "protected" or "private", they're still public. | |||

====<span id='Protected_Attributes'></span>"Protected" Attributes==== | |||

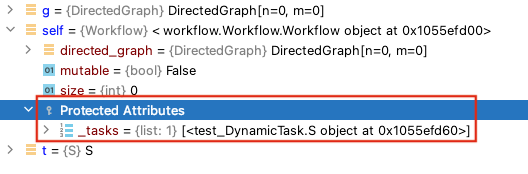

Prepending a single underscore (_) to the attribute name provides some support for protecting module variables and functions, as well as class attributes and methods. Linters and IDE static analysis will flag protected member access. PyCharm explicitly shows them as "Protected Attributes": | |||

:::[[File:PyCharm_Protected_Attributes.png]] | :::[[File:PyCharm_Protected_Attributes.png]] | ||

Also see [[#Read-Only_Properties|Read-Only Properties]], below, and: {{Internal|Python_Language#Leading_Underscore_Variable_Names|Python Language | Leading Underscore Variable Names}} | |||

< | ====<span id='Private_Attributes'></span><span id='Private_Attribute'></span><span id='Mangling_Attribute_Names_for_Privacy'></span>"Private" Attributes==== | ||

Prepending a double underscore (__) (also known as “dunder”) to an instance variable or method effectively makes the variable or method private to its class, using name mangling. [https://google.github.io/styleguide/pyguide.html#3162-naming-conventions Google Python Style Guide] discourages this use as it impacts readability and testability, and isn’t really private. It advises to use a [[#.22Protected.22_Attributes|single underscore]]. | |||

=== | ==<span id='Class_Attribute'></span><span id='Class_Attributes'></span>Class (Static) Attributes== | ||

< | |||

</ | |||

Python does not have a <code>static</code> keyword to declare a static attribute (variable). Simply declaring the attribute inside the class, and avoiding to declare it inside any method, makes it a static, or a class attribute: | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | <syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | ||

class A: | class A: | ||

COLOR = 'red' | |||

@staticmethod | |||

def my_class_color(): | |||

return A.COLOR | |||

assert A.my_class_color() == 'red' | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

=<span id='Property'></span><span id='Getters_and_Setters'></span>Properties= | |||

A property is semantically equivalent with an attribute, in that is supposed to give read and write access to some state associated with the class instance. However, it does not do it by simply designating a variable to hold the state. It does it by defining the accessors and mutators (getters and setters) methods instead. Properties are customizable [[#Attribute|attributes]]. | |||

An advantage of using properties over direct attribute access is that if the definition of the attribute changes, only the code within the class definition needs to be changed, not the caller code. | |||

There are two ways to declare the accessor, mutator and deleted method for state associated with the class instance: using the <code>[[#property_builtin|property()]]</code> built-in and using [[#Decorators|decorators]]. | |||

==<span id='The_property.28.29_Built-in_Function'></span><span id='property_builtin'></span>Defining Properties with the <tt>property()</tt> Built-in Function== | |||

The <code>[[Python_Language_Functions#property|property()]]</code> built-in function defines a class construct that acts like a virtual attribute, or a proxy to an attribute, by defining the accessor (getter) function, and optionally the mutator (setter), and proxying any requests to set or access the attribute through those methods. The <code>[[Python_Language_Functions#property|property()]]</code> built-in function also allows to declare an optional deleter function, and a [[Python_Language_Functions#Docstring|docstring]] for the property. If the docstring is not provided, it will be copied from the docstring of the first argument, the getter method. The <code>[[Python_Language_Functions#property|property()]]</code> is like a constructor for such a proxy, and the proxy is set as a public-facing member for the given attribute. | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | <syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | ||

class SomeClass: | |||

def __init__(self): | |||

self._internal_state = None | |||

def _some_getter(self): | |||

return self._internal_state | |||

def _some_setter(self, value): | |||

self._internal_state = value | |||

def _some_deleter(self): | |||

pass | |||

some_property = property(_some_getter, _some_setter, _some_deleter, "this is docstring") | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

==== | Use <code>some_property</code> as it was an attribute. Internally, <code>some_property</code> calls the <code>_some_getter()</code> and <code>_some_setter()</code> methods whenever the value of the property is accessed or changed. | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | |||

sc = SomeClass() | |||

sc.some_property = 'elephant' | |||

assert sc.some_property == 'elephant' | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

< | ⚠️ Do not use the property name as it would be a method name. <code>sc.some_property('elephant')</code> will raise an exception: | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang='text'> | |||

TypeError: 'NoneType' object is not callable | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

==<span id='Decorators'></span>Defining Properties with Decorators== | |||

A fully equivalent pattern of declaring a property as a proxy to a virtual attribute uses the <code>@property</code> decorator, to designate the getter method, the <code>@<attribute-name>.setter</code> decorator to designate the setter method, and the <code><attribute-name>.deleter</code> decorator to designate the deleter method. The setter and the deleter are optional. | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | <syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | ||

class | class SomeClass: | ||

def __init__(self): | |||

self._internal_state = None | |||

# The corresponding attribute name will be "some_property", | |||

# the same as the name of the getter method. ⚠️ The name | |||

# of the method must match the name of the attribute. | |||

@property | |||

def some_property(self): | |||

return self._internal_state | |||

# The corresponding attribute name will be "some_property", the same as | |||

# the decorator prefix AND the name of the setter method. ⚠️ The decorator | |||

# prefix must match the name of the setter method and that of the attribute | |||

@some_property.setter | |||

def some_property(self, value): | |||

self._internal_state = value | |||

@some_property.deleter | |||

def some_property(self): | |||

pass | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

Use <code>some_property</code> as it was an attribute. Internally, <code>some_property</code> calls the <code>some_property()</code> and <code>some_property(value)</code> methods whenever the value of the property is accessed or changed. | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | <syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | ||

sc = SomeClass() | |||

sc.some_property = 'elephant' | |||

assert sc.some_property == 'elephant' | |||

assert ' | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

⚠️ Do not use the property name as it would be a method name. <code>sc.some_property('elephant')</code> will raise an exception: | |||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang='text'> | ||

TypeError: 'NoneType' object is not callable | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

We cannot specify a docstring using property decorators, so we need to rely on the property copying the docstring from the initial getter method. | |||

<font color=darkkhaki>Using the same name for the getter and setter methods is not required, but it does help to group together visually the multiple methods that refer to one property.</font> | |||

= | The syntax: | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | |||

@property | |||

def some_property(self): | |||

... | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

applies the <code>property()</code> function as a decorator, and it is equivalent with the following syntax: | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang='py'> | |||

some_property = property(some_property) | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

The main difference, from a readability perspective, is that we gt to mark the <code>some_property()</code> function as a property at the top of its declaration, instead of after it was defined, where it can be easily overlooked. It also means we don't have to create private methods with underscore prefixes just to define a property. This is way the decorator-based syntax is preferable. | |||

For more details on decorators see: {{Internal|Python_Decorators#Overview|Python Decorators}} | |||

==Read-Only Properties== | |||

The state associated with a computed value can be prevented from being written by omitting the corresponding setter. | |||

However, if properties are used to proxy access to an internal variable, the pattern is not entirely safe, even if the setter is omitted: the internal variable can still be accessed directly, as all attributes are public in Python. However, marking the internal variable with [[#.22Protected.22_Attributes|a leading underscore]] is an indication that the variable should not be accessed directly. | |||

However, | |||

</ | =Introspection with <tt>getattr()</tt>, <tt>hasattr()</tt> and </tt>setattr()</tt>= | ||

Attributes and methods can be accessed by name via <code>getattr()</code> and <code>hasattr()</code> functions, and modified with <code>setattr()</code>. For more details see: {{Internal|Python_Introspection#Builtin_Introspection_Functions|Python Introspection}} | |||

Latest revision as of 22:58, 15 May 2024

Internal

Overview

Attributes are variables associated with a class that carry state either for the class itself, or for the instances of that class. They are other Python objects stored "inside" the object.

Properties are class constructs that behave like attributes, but are not variables. Technically, bona-fide attributes, properties and also the methods are all attributes on a class. Methods are just callable attributes. For a discussion on how to decide between attributes and properties, see When to Use Attributes and When to Use Properties.

When to Use Attributes and When to Use Properties

Always use a standard attribute until you need to control access to it in some way. The only difference between an attribute and a property is that we can invoke custom actions automatically when a property is retrieved, set or deleted.

Properties are useful when the values need to be cached. The first time the value is retrieved, the lookup and the calculation is performed. Then, the value can be cached locally, so the next time the value is requested, we return the stored data.

Custom getters are also useful for attributes that need to be calculated on the fly, based on other object attributes.

Custom setters are useful for validation. They can be used to proxy a value to another location.

Attributes

Attributes are variables associated with a class that hold state either for the instances of that class (instance attributes) or for the class itself (class attributes). An object instance carries its state as attributes. To differentiate attributes from properties, they are sometimes referred to as standard data attributes.

Instance Attributes

Declaring Instance Attributes

All instance attributes must be declared inside the __init__() method.

class A:

def __init__(self):

self.color = 'blue'

If an attribute is first used in a method other than __init__(), static analysis identifies this as a warning "instance attribute defined outside __init__()".

Accessing and Mutating Instance Attributes

Idiomatic Python favors direct attribute access. The instance attributes can be accessed and mutated inside the class definition using self.<attribute-name>. Outside the class definition, they can be accessed and mutated via the variable holding the reference to the class instance: my_instance.<attribute-name>. If an attribute was not explicitly declared inside the instance with self.some_attribute, even just to be assigned to None, an attempt to access the attribute will end up in:

AttributeError: 'MyClass' object has no attribute 'some_attribute'

Deleting Instance Attributes

An attribute can also be deleted, meaning that it will be removed from the instance it was deleted from.

class A:

def __init__(self):

self.color = 'blue'

def delete_attr(self):

del self.color

a = A()

a2 = A()

a2.delete_attr()

print(a.color) # this will display "blue"

print(a2.color) # this will raise AttributeError: 'A' object has no attribute 'color'

Deleting instance attributes has limited usefulness.

Attribute Visibility

Unlike in other languages, all attributes are public in Python. There are naming conventions to designate attributes as protected, or even private, but these conventions depend on others' willingness to abide by them - the interpreter won't prevent access to an attribute conventionally declared "protected" or "private", they're still public.

"Protected" Attributes

Prepending a single underscore (_) to the attribute name provides some support for protecting module variables and functions, as well as class attributes and methods. Linters and IDE static analysis will flag protected member access. PyCharm explicitly shows them as "Protected Attributes":

Also see Read-Only Properties, below, and:

"Private" Attributes

Prepending a double underscore (__) (also known as “dunder”) to an instance variable or method effectively makes the variable or method private to its class, using name mangling. Google Python Style Guide discourages this use as it impacts readability and testability, and isn’t really private. It advises to use a single underscore.

Class (Static) Attributes

Python does not have a static keyword to declare a static attribute (variable). Simply declaring the attribute inside the class, and avoiding to declare it inside any method, makes it a static, or a class attribute:

class A:

COLOR = 'red'

@staticmethod

def my_class_color():

return A.COLOR

assert A.my_class_color() == 'red'

Properties

A property is semantically equivalent with an attribute, in that is supposed to give read and write access to some state associated with the class instance. However, it does not do it by simply designating a variable to hold the state. It does it by defining the accessors and mutators (getters and setters) methods instead. Properties are customizable attributes.

An advantage of using properties over direct attribute access is that if the definition of the attribute changes, only the code within the class definition needs to be changed, not the caller code.

There are two ways to declare the accessor, mutator and deleted method for state associated with the class instance: using the property() built-in and using decorators.

Defining Properties with the property() Built-in Function

The property() built-in function defines a class construct that acts like a virtual attribute, or a proxy to an attribute, by defining the accessor (getter) function, and optionally the mutator (setter), and proxying any requests to set or access the attribute through those methods. The property() built-in function also allows to declare an optional deleter function, and a docstring for the property. If the docstring is not provided, it will be copied from the docstring of the first argument, the getter method. The property() is like a constructor for such a proxy, and the proxy is set as a public-facing member for the given attribute.

class SomeClass:

def __init__(self):

self._internal_state = None

def _some_getter(self):

return self._internal_state

def _some_setter(self, value):

self._internal_state = value

def _some_deleter(self):

pass

some_property = property(_some_getter, _some_setter, _some_deleter, "this is docstring")

Use some_property as it was an attribute. Internally, some_property calls the _some_getter() and _some_setter() methods whenever the value of the property is accessed or changed.

sc = SomeClass()

sc.some_property = 'elephant'

assert sc.some_property == 'elephant'

⚠️ Do not use the property name as it would be a method name. sc.some_property('elephant') will raise an exception:

TypeError: 'NoneType' object is not callable

Defining Properties with Decorators

A fully equivalent pattern of declaring a property as a proxy to a virtual attribute uses the @property decorator, to designate the getter method, the @<attribute-name>.setter decorator to designate the setter method, and the <attribute-name>.deleter decorator to designate the deleter method. The setter and the deleter are optional.

class SomeClass:

def __init__(self):

self._internal_state = None

# The corresponding attribute name will be "some_property",

# the same as the name of the getter method. ⚠️ The name

# of the method must match the name of the attribute.

@property

def some_property(self):

return self._internal_state

# The corresponding attribute name will be "some_property", the same as

# the decorator prefix AND the name of the setter method. ⚠️ The decorator

# prefix must match the name of the setter method and that of the attribute

@some_property.setter

def some_property(self, value):

self._internal_state = value

@some_property.deleter

def some_property(self):

pass

Use some_property as it was an attribute. Internally, some_property calls the some_property() and some_property(value) methods whenever the value of the property is accessed or changed.

sc = SomeClass()

sc.some_property = 'elephant'

assert sc.some_property == 'elephant'

⚠️ Do not use the property name as it would be a method name. sc.some_property('elephant') will raise an exception:

TypeError: 'NoneType' object is not callable

We cannot specify a docstring using property decorators, so we need to rely on the property copying the docstring from the initial getter method.

Using the same name for the getter and setter methods is not required, but it does help to group together visually the multiple methods that refer to one property.

The syntax:

@property

def some_property(self):

...

applies the property() function as a decorator, and it is equivalent with the following syntax:

some_property = property(some_property)

The main difference, from a readability perspective, is that we gt to mark the some_property() function as a property at the top of its declaration, instead of after it was defined, where it can be easily overlooked. It also means we don't have to create private methods with underscore prefixes just to define a property. This is way the decorator-based syntax is preferable.

For more details on decorators see:

Read-Only Properties

The state associated with a computed value can be prevented from being written by omitting the corresponding setter.

However, if properties are used to proxy access to an internal variable, the pattern is not entirely safe, even if the setter is omitted: the internal variable can still be accessed directly, as all attributes are public in Python. However, marking the internal variable with a leading underscore is an indication that the variable should not be accessed directly.

Introspection with getattr(), hasattr() and setattr()

Attributes and methods can be accessed by name via getattr() and hasattr() functions, and modified with setattr(). For more details see: