OpenShift Concepts TODEPLETE: Difference between revisions

(→Volume) |

|||

| Line 452: | Line 452: | ||

{{Internal|OpenShift Volume Concepts|Volumes}} | {{Internal|OpenShift Volume Concepts|Volumes}} | ||

===Persistent Volume Claim=== | ===Persistent Volume Claim=== | ||

Revision as of 01:21, 6 February 2018

External

Internal

Overview

The OpenShift is a Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) based on industry standards. It provides development environments on demand. It is a polyglot offering, including a range of languages, frameworks, runtimes and databases. It automates management of the entire application life cycle: build, deploy and retire. It enables collaboration between developers on projects.

OpenShift is PaaS by RedHat: an enterprise-grade, secure, multi-language, auto-scaling, self-service, elastic could application platform, automated with CI/CD and built on Red Hat technologies.

OpenShift is supported anywhere RHEL is: bare metal, virtualized infrastructure (Red Hat Virtualization, vSphere, Hyper-V), OpenStack platform, public cloud providers (Amazon, Google, Azure). It runs on RHEL and Red Hat Atomic.

OpenShift extends Kubernetes to provide a more feature rich development lifecycle platform.

OpenShift Workflow

Users or automation make calls to the REST API via the command line, web console or programmatically, to change the state of the system. The master analyses the state changes and acts to bring the state of the system in sync with the desired state. The state is maintained in the store layer. Most OpenShift commands and API calls do not require the corresponding actions to be performed immediately. They usually create or modify a resource description in etcd. etcd then notifies Kubernetes or the OpenShift controllers, which notify the resource about the change. Eventually, the system state reflects the change.

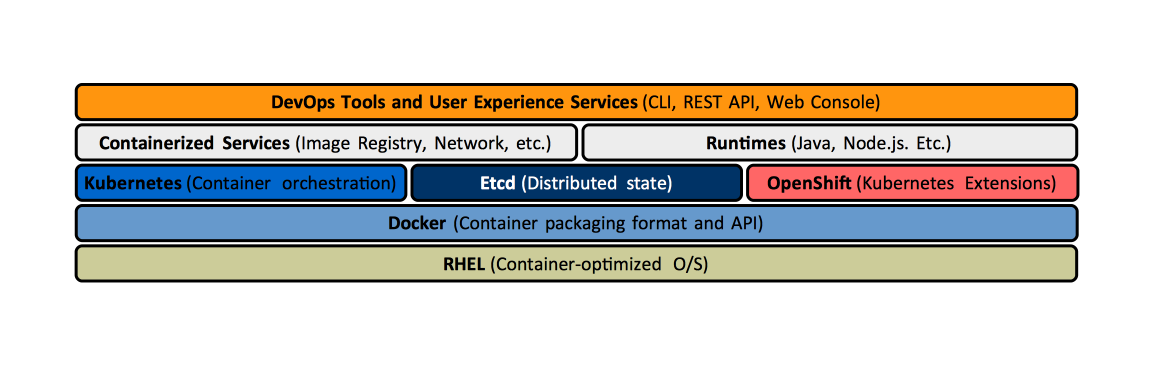

OpenShift functionality is provided by the interaction of several layers:

- The store layer holds the state of the OpenShift environment, which includes configuration information, current state and the desired state. It is implemented by etcd.

- The authentication layer provides a framework for collaboration and quota management.

- Scheduling is OpenShift master's main function and it is implemented in the scheduling layer, which contains the scheduler.

- The service layer handles internal requests. It provides an abstraction of service endpoints and provides internal load balancing. The pods get IP addresses associated with the service endpoints. Note that the external requests are not handled by the service layer, but by the routing layer.

- The routing layer handles external requests, to and from the applications. For a description of the relationship between a service and a router, see relationship between a service and router.

- Application requests are routed to the business logic serving them according to the networking workflow, by the networking layer.

- The replication layer contains the replication controller, whose role is to ensure that the number of instances and pods defined in the store layer actually exists.

Objects

Core Objects

Defined by Kubernetes, and also used by OpenShift. All these objects have an API type, which is listed below.

- Projects (oc get project), defined by Project.

- Pods (oc get pods) defined by Pod.

- Nodes (oc get nodes) defined by Node.

- Deployment Configurations (oc get dc) defined by DeploymentConfig.

- Services (oc get svc) defined by Service.

- Routes (oc get route) defined by Route.

- Replication Controllers (oc get rc) defined by ReplicationController.

- Secrets (oc get secret) defined by Secret.

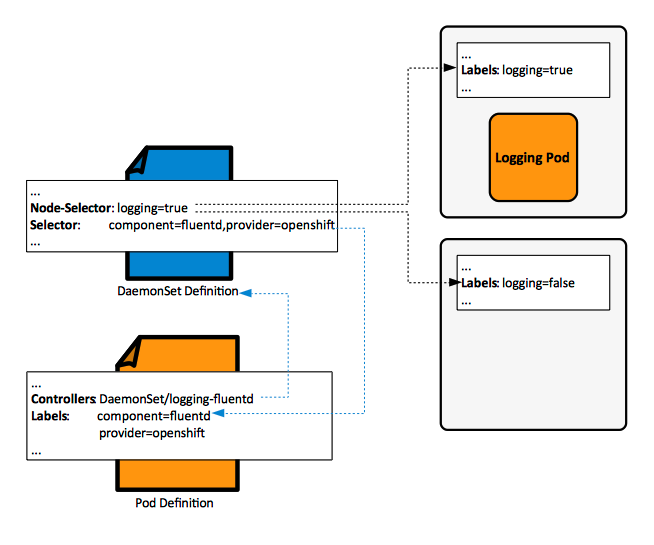

- Daemon Sets.

OpenShift Objects

Defined by OpenShift, outside Kubernetes. These objects also have an API type, which is listed below.

- Images defined by Image.

- Image Streams (oc get is) defined by ImageStream.

- Image Stream Tags (oc get istag).

- Builds (oc get build).

- Build Configurations (oc get bc) defined by BuildConfig.

- Templates defined by Template.

- OAuthClient.

Other Objects that do not have an API Representation

OpenShift Hosts

Master

A master is a RHEL or Red Hat Atomic host that orchestrates and schedules resources.

The master maintains the state of the OpenShift environment.

The master provides the single API all tooling clients must interact with. All OpenShift tools (CLI, web console, IDE plugins, etc. speak directly with the master).

The access is protected via fine-grained role-based access control (RBAC).

The master monitors application health via user-defined pod probes, insuring that all containers that should be running are running. It handles restarting pods that failed probes automatically. Pods that fail too often are marked as "failing" and are temporarily not restarted. The OpenShift service layer sends traffic only to healthy pods.

Masters use the etcd cluster to store state, and also cache some of the metadata in their own memory space.

Master HA

Multiple masters can be present to insure HA. A typical HA configuration involves three masters and three etcd nodes. Such a topology is built by the OpenShift 3.5 ansible inventory file shown here.

An alternative HA configuration consists in a single master node and multiple (at least three) etcd nodes.

The native HA Method

Master API

The master API is available internally (inside the OpenShift cluster) at https://openshift.default.svc.cluster.local This value is available internally to pods as the KUBERNETES_SERVICE_HOST environment variable.

Node

A node is a Linux container host. It is based on RHEL or Red Hat Atomic and provides a runtime environment where applications run inside containers, which run inside pods assigned by the master. Nodes are orchestrated by masters and are usually managed by administrators and not by end users. Nodes can be organized into different topologies. From a networking perspective, nodes gets allocated their own subnets of the cluster network, which then they use to distribute to the pods, and containers, running on them. More details about OpenShift networking is available here.

A node daemon runs on node each node.

Node operations:

TODO:

- What is the difference between the kubelet and the node daemon?

- kube proxy daemons.

Infrastructure Node

Also referred to as "infra node".

This is where infrastructure pods run. Metrics, logging, routers are considered infrastructure pods.

The infrastructure nodes, especially those running the the metrics pods and ... should be closely monitored to detect early CPU, memory and disk capacity shortages on the host system.

OpenShift Cluster

All nodes that share the SDN.

Container

A container is a kernel-provided mechanism to run one or more processes, in a portable manner, in a Linux environment. Containers are isolated from each other on a host and are initialized from images. All application instances - based on various languages/frameworks/runtimes - as well as databases, run inside containers on nodes. For more details, see

A pod can have application containers and init containers.

In OpenShift, containers are never restarted. Instead, new containers are spun up to replace old containers when needed. Because of this behavior, persistent storage volumes mounted on containers are critical for maintaining state such as for configuration files and data files.

Init Container

Docker Support in OpenShift

All containers that are running in pods are managed by Docker servers.

Docker Storage in OpenShift

Each Docker server requires Docker storage, which is allocated on each node in a space specially provisioned as Docker storage backend. The Docker storage is ephemeral and separate from OpenShift storage. The default loopback storage back end for Docker is a thin pool on loopback devices, which is not appropriate for production.

The node Daemon

Pod

A pod is a set of one or more containers, deployed together onto a node, as a single unit.

The defining characteristic of a pod is that all its containers share a virtual network device - an unique IP -, and a set of persistent volumes. Pods also define the security and runtime policy for each container.

The "pod" is a Kubernetes concept, for more details, see Kubernetes Pods. Each pod gets a pod IP address that is routable by default from any other pod in the environment. The default addresses are part of the 10.x.x.x set. The containers on a pod share the IP address and TCP ports, because they share the pod's virtual network device. They also share persistent storage volumes, and other resources allocated to the pod. The pod contains collocated applications that are relatively tightly coupled and run with a shared context. Within that context, an application may have individual cgroups isolation applied. A pod models an application-specific logical host, containing applications that in a pre-container world would have run on the same physical or virtual host, and in consequence, the pod cannot span hosts. The pod is the smallest unit that can be defined, deployed and managed by OpenShift. Complex applications can be made of any number of pods, and OpenShift helps with pod orchestration. Pods do not maintain state, they are expendable.

Pods must not created or managed directly, but by their controllers, which are specified in the pod description.

OpenShift treats pods as largely immutable - changes cannot be made to a pod definition while the pod is running - and expendable, they do not maintain state when they are destroyed and recreated. Therefore, they are managed by controllers, not directly by users.

The pods for a project are displayed by the following commands:

oc get all oc get pods

Pods for a project can also be viewed in the web console to the project -> Applications -> Pods.

A pod executing a container based on a simple image, suited for experimentation, can be created as described here: "Simple Pod Running inside an OpenShift Project".

Controller

A controller is the OpenShift component that creates and manages pods. The controller of a pod is reported by oc describe pod command, under the "Controllers" section:

... Controllers: ReplicationController/logging-kibana-1 ...

The most common controllers are:

Pod Configuration

Pods are treated as static, and cannot be changed while they are running. To change a pod, the current pod must be terminated, and a new one with a modified base image and/or configuration must be created.

Pod Lifecycle

- A pod is defined in a pod definition.

- A pod is instantiated and assigned to run on a node as a result of the scheduling process.

- The pod runs until its containers exit or the pod is removed.

- Depending on policy and exit code, may be removed or retained to enable access to their container's logs.

Terminal State

A pod is in a terminal state if "status.phase" is either "Failed" or "Succeeded".

Pod Definition

The definition of an already existing pod can be obtained with oc describe pod.

Pod Name

Pod must have an unique name in their namespace (project). The pod definition can specify a base name and use "generateName" attribute to append random characters at the end of the base name, thus generating an unique name.

Pod Definition File

Pod Placement

Pods can be configured to execute on a specific node, defined by the node name, or on nodes that match a specific node selector.

To assign a pod to a specific node, TODO https://docs.openshift.com/container-platform/3.5/admin_guide/scheduler.html#constraining-pod-placement-labels

To assign a pod to nodes that match a node selector, add the "nodeSelector" element in the pod configuration, with a value consisting in key/value pairs, as described here:

After a successful placement, either by a replication controller or by a DaemonSet, the pod records the successful node selector expression as part of its definition, which can be rendered with oc get pod -o yaml:

spec: ... nodeSelector: logging: "true" ...

Consolidate with OpenShift_Concepts#Node_Selector

Pod Probe

Users can configure pod probes for liveness or readiness. Can be configured with:

- initialDelaySeconds

- timeoutSeconds (default 1)

Liveness Probe

A liveness probe is deployed in a container to expose whether the container is running. Examples of liveness probes: commands executed inside the container, tcpSocket.

livenessProbe: {

initialDelaySeconds: 30,

timeoutSeconds: 1

periodSeconds: 10,

failureThreshold: 3,

successThreshold: 1,

tcpSocket: {

port: 5432

},

}

Readiness Probe

A readiness probe is deployed in a container to expose whether the container is ready to service requests.

Readines probes: httpGet.

readinessProbe:

initialDelaySeconds: 5

timeoutSeconds: 1

periodSeconds: 10

failureThreshold: 3

successThreshold: 1

exec:

command:

- /bin/sh

- -i

- -c

- psql -h 127.0.0.1 -U $POSTGRESQL_USER -q -d $POSTGRESQL_DATABASE -c 'SELECT 1'

Local Manifest Pod

Bare Pod

A pod that is not backed by a replication controller. Bare pods cannot be evacuated from nodes.

Pod Type

Terminating

A terminating pod has non-zero positive integer as value of "spec.activeDeadlineSeconds". Builder or deployer pods are terminating pods. The pod type can be specified as scope for resource quotas.

NonTerminating

A non-terminating pod has no "spec.activeDeadlineSeconds" specification (nil). Long running pods as a web server or a database are non-terminating pods. The pod type can be specified as scope for resource quotas.

Label

Labels are simple key/value pairs that can be assigned to any resource in the system and are used to group and select arbitrarily related objects. Most Kubernetes objects can include labels in their metadata. Labels provide the default way of manage objects as groups, instead of having to handle each object individually. Labels are a Kubernetes concept.

Labels associated with a node can be obtained with oc describe node.

Selector

A selector is a set of labels. It is also referred to as label selector. Selectors are a Kubernetes concept.

Node Selector

A node selector is an expression applied to a node, which, depending on whether the node has or does not have the labels expected by the node selector, allows or prevents pod placement on the node in question during the pod scheduling operation. It is the scheduler that evaluates the node selector expression and decides on which node to place the pod. The DaemonSets also use node selectors when placing the associated pods on nodes.

Node selectors can be associated with an entire cluster, with a project, or with a specific pod. The node selectors can be modified as part of a node selector operation.

Cluster-Wide Default Node Selector

The cluster-wide default node selector is configured during OpenShift cluster installation to restrict pod placement on specific nodes. It is specified in the projectConfig.defaultNodeSelector section of the master configuration file master-config.yml. It can also be modified after installation with the following procedure:

Per-Project Node Selector

The per-project node selector is used by the scheduler to schedule pods associated with the project. The per-project node selector and takes precedence over cluster-wide default node selector, when both exist. It is available as "openshift.io/node-selector" project metadata (see below). If "openshift.io/node-selector" is set to an empty string, the project will not have an adminstrator-set node selector, even if the cluster-wide default has been set. This means that a cluster administrator can set a default to restrict developer projects to a subset of nodes and still enable infrastructure or other projects to schedule the entire cluster.

The per-project node selector value can be queried with:

oc get project -o yaml

It is listed as:

...

kind: Project

metadata:

annotations:

...

openshift.io/node-selector: ""

...

The per-project node selector is usually set up when the project is created, as described in this procedure:

It can also be changed after project creation with oc edit as described in this procedure:

Per-Pod Node Selector

The declaration of a per-pod node selector can be obtained running:

oc get pod <pod-name> -o yaml

and it is rendered in the "spec:" section of the pod definition:

...

kind: Pod

spec:

...

nodeSelector:

key-A: value-A

How is the node selector of a pod generated?

TODO: merge with OpenShift_Concepts#Pod_Placement

Once the pod has been created, the node selector value becomes immutable and an attempt to change it will fail. For more details on pod state see Pods.

Precedence Rules when Multiple Node Selectors Apply

TODO

External Resources

Scheduler

Scheduling is the master's main function: when a pod is created, the master determines on what node(s) to execute the pod. This is called scheduling. The layer that handles this responsibility is called the scheduling layer.

The scheduler is a component that runs on master and determines the best fit for running pods across the environment. The scheduler also spreads pod replicas across nodes, for application HA. The scheduler reads data from the pod definition and tries to find a node that is a good fit based on configured policies. The scheduler does not modify the pod, it creates a binding that ties the pod to the selected node, via the master API.

The OpenShift scheduler is based on Kubernetes scheduler.

Most OpenShift pods are scheduled by the scheduler, unless they are managed by a DaemonSet. In this case, the DaemonSet selects the node to run the pod, and the scheduler ignores the pod.

The scheduler is completely independent and exists as a standalone, pluggable solution. The scheduler is deployed as a container, referred to as an infrastructure container. The functionality of the scheduler can be extended in two ways:

- Via enhancements, by adding predicates to the priority functions.

- Via replacement with a different implementation.

The pod placement process is described here:

Default Scheduler Implementation

The default scheduler is a scheduling engine that selects the node to host the pod in three steps:

- Filter all available nodes by running through a list of filter functions called predicates, discarding the nodes that do not meet the criteria.

- Prioritize the remaining nodes by passing through a series of priority functions that assigns each node a score between 0 - 10. 10 signifies the best possible fit to run the pod. By default all priority function are considered equivalent, but they can be weighted differently via configuration.

- Sorts the node by score and selects the node with the highest score. If multiple nodes come with the same score, one is chosen at random.

Note that an insight into how the predicates are evaluated and what scheduling decisions are taken can be achieved by increasing the logging verbosity of the master controllers processes.

Predicates

Static Predicates

- PodFitsPorts - a node is fit fi there are no port conflicts.

- PodFitsResources - a node is fit based on resource availability. Nodes declare resource capacities, pods specify what resources they require.

- NoDiskConflict - evaluates if a pod fits based on volumes requested and those already mounted.

- MatchNodeSelector - a node is fit based on the node selector query.

- HostName - a node is fit based on the presence of host parameter and string match with host name.

Configurable Predicates

ServiceAffinity

ServiceAffinity filters out nodes that do not belong to the topological level defined by the provided labels. See scheduler.json

LabelsPresence

LabelsPresence checks whether the node has certain labels defined, regardless of value.

Priority Functions

Existing Priority Functions

- LeastRequestedPriority - favors nodes with fewer requested resources, calculates percentage of memory and CPU requested by pods scheduled on node, and prioritizes nodes with highest available capacity.

- BalancedResourceAllocation - favors nodes with balanced resource usage rate, calculates difference between consumed CPU and memory as fraction of capacity and prioritizes nodes with the smallest difference. It should always be used with LeastRequestedPriority.

- ServiceSpreadingPriority - spreads pods by minimizing the number of pods that belong to the same service, onto the same node

- EqualPriority

Configurable Priority Functions

- ServiceAntiAffinity

- LabelsPreference

Scheduler Policy

The selection of the predicates and the priority functions defines the scheduler policy. The default policy is configured in the master configuration file master-config.yml as kubernetesMasterConfig.schedulerConfigFile. By default, it points to /etc/origin/master/scheduler.json. The current scheduling policy in force can be obtained with ?. A custom policy can replace it, if necessary, by following this procedure: Modify the Scheduler Policy.

Scheduler Policy File

The default scheduler policy is configured in the master configuration file master-config.yml as kubernetesMasterConfig.schedulerConfigFile, which by default points to /etc/origin/master/scheduler.json. Another example of scheduler policy file:

Volumes

Persistent Volume Claim

A persistent volume claim is a request for a persistence resource with specific attributes, such as storage size. Persistent volume claims are matched to available volumes and binds the pod to the volume. This process allows a claim to be used as a volume in a pod: OpenShift finds the volume backing the claim and mounts it into the pod. Persistent volume claims are project-specific objects.

The pod can be disassociated from the persistent volume by deleting the persistent volume claim. The persistent volume transitions from a "Bound" to "Released" state. To make the persistent volume "Available" again, edit it and remove the persistent volume claim reference, as shown here. Transitioning the persistent volume from "Released" to "Available" state does not clear the storage content - this will have to be done manually.

All persistent volume claims for the current project can be listed with:

oc get pvc

Temporary Pod Volume

When temporary pod volumes are used, the data is written to /var/lib/origin/openshift.local.volumes/pods on the node where the pod is running.

EmptyDir

An "emptyDir" volume is created when the pod is assigned to a node, and exists as long as the pod is running on the node. It is initially empty. Containers in a pod can all read and write the same files in the "emptyDir" volume, though the volume can be mounted at the same or different paths in each container.

When the pod is removed from the node, the data is deleted. If the container crashes, that does not remove the pod from a node, so data in an empty dir is safe across container crashes.

The "emptyDir" volumes are stored on whatever medium is backing the node (disk, network storage). The mapping on the local file system backing the node can be discovered by identifying the container and then executing a docker inspect:

"Mounts": [

{

"Source": "/var/lib/origin/openshift.local.volumes/pods/1806c74f-0ad4-11e8-85a1-525400360e56/volumes/kubernetes.io~empty-dir/emptydirvol1",

"Destination": "/something",

"Mode": "Z",

"RW": true,

"Propagation": "rprivate"

}

...

EmptyDir Operations

etcd

Implements OpenShift's store layer, which holds the current state, desired state and configuration information of the environment.

OpenShift stores image, build, and deployment metadata in etcd. Old resources must be periodically pruned. If a large number of images/build/deployments are planned, etcd must be placed on machines with large amounts of memory and fast SSD drives.

etcd and Master Caching

Masters cache deserialized resource metadata to reduce the CPU load and keep the metadata in memory. For small clusters, the cache can use a lot of memory for negligible CPU reduction. The default cache size is 50,000 entries, which, depending on the size of resources, can grow to occupy 1 to 2 GB of memory. The cache size can be configured in master-config.yml.

Image Registries

Integrated Docker Registry

OpenShift contains an integrated Docker image registry, providing authentication and access control to images. The integrated registry should not be confused with the OpenShift Container Registry (OCR), which is a standalone solution, which can be used outside of an OpenShift environment. The integrated registry is an application deployed within the "default" project as a privileged container, as part of the cluster installation process. The integrated registry is available internally in the OpenShift cluster at the following Service IP: docker-registry.default.svc:5000/. It consists of a a "docker-registry" service, a "docker-registry" deployment configuration, a "registry" service account and a role binding that associates the service account to the "system:registry" cluster role. More details on the structure of the integrated registry can be generated with oadm registry -o yaml. The default registry also comes with a registry console that can be used to browse images.

The main function of the integrated registry is to provide a default location where users can push images they build. Users push images into registry and whenever a new image is stored in the registry, the registry notifies OpenShift about it and passes along image information such as the namespace, the name and the image metadata. Various OpenShift components react by creating new builds and deployments.

Alternatively, the integrated registry may store and expose to projects external images the projects may need. The docker servers on OpenShift nodes are configured to be able to access the internal registry, but they are also configured with registry.access.redhat.com and docker.io.

Questions:

- How can I "instruct" an application to use a specific registry. a “lab” application to use registry-lab

- How do pods that need images go to that registry and not other? The answer to this question lays in the way an application uses the registry.

External Registries

The external registries registry.access.redhat.com and docker.io are accessible. In general, any server implementing Docker registry API can be integrated as a stand-alone registry.

registry.access.redhat.com

The Red Hat registry is available at http://registry.access.redhat.com. An individual image can be inspected with an URL similar to https://access.redhat.com/containers/#/registry.access.redhat.com/jboss-eap-7/eap70-openshift/images/1.5-23

docker.io

Docker Hub is available at http://dockerhub.com.

Stand-alone Registry

Any server implementing Docker registry API can be integrated as a standalone registry: a stand-alone container registry can be installed and used with the OpenShift cluster.

Integrated Registry Console

The registry comes with a "registry console" that allows web-based access to the registry. An URL example is https://registry-console-default.apps.openshift.novaordis.io. The registry console is deployed as a registry-console pod part of the "default" project.

Registry Operations

Service

A service represents a group of pods, which may individually come and go, and its primary function is to provide the permanent IP, hostname and port for other applications to use. Each service has a service IP address and a port, which is allocated from the services subnet. The service IP address is sometimes referred to as the "Cluster IP", which is consistent with the abstraction provided by the service: a cluster of OpenShift-managed pods providing the service. The services constitute the service layer.

If the service definition includes a selector, that selector is used to identify the pods that are part of the service's "cluster". The EndpointsController system component associates a service with the endpoints of pods that match the selector. Once the association is done, the actual physical network streaming is performed by a service proxy. More about endpoints is available here: service endpoints.

In some special cases, the service can represent a set of pods running outside the current project, or an instance running outside OpenShift altogether. Services representing external resources do not require associated pods, hence do not need a selector. They are called external services. If the selector is not set, the EndpointsController ignores the services, and endpoints can be specified manually. The procedure to declare services from another projects or external service is available here:

The service IP is available internally in the cluster. It is not routable (in the IP sense) externally. The service can be exposed externally via a route.

A service resource is an abstraction that defines a logical set of pods and a policy that is used to access the pods. The service layer is how applications communicate with one another. The service is a Kubernetes concept. The service serves as an internal load balancer: it identifies a set of replicated pods and then proxies the connections it receives to those pods (routers provide external load balancing). The service is not a "thing", but an entry in the configuration. Backing pods can be added or removed to or from the service arbitrarily. This way, anything that depends on the service can refer to it as a consistent IP:port pair. The services uses a label selector to find all the running containers associated with it.

Services can be consumed from other pods using the values of the <SERVICE>_HOST environment variables that are injected by the cluster.

Services of a project can be displayed with:

oc get all oc get svc

Service Endpoint

An <pod IP address>:<port> pair that corresponds to a process running inside of a container, on a pod, on a node. The process that associates services and endpoints is performed by the EndpointController and it is described above. The service endpoint coordinate can be obtained by executing:

oc describe service <service-name>

Name: logging-kibana ... Endpoints: 10.129.2.17:3000 ...

Service Proxy

The service proxy is a simple network proxy that represents the services defined in the API on the node. Each node runs a service proxy instance. The service proxy does simple TCP and UDP stream forwarding across a set of backends.

Service Dependencies

TODO: It seems there's a way to express dependencies between services:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: jenkins

annotations:

service.alpha.openshift.io/dependencies: '[{"name": "jenkins-jnlp", "namespace": "", "kind": "Service"}]'

...

spec:

...

Clarify this.

Relationship between Services and the Pods providing the Service

API

Networking

Required Network Ports

Default Network Interface on a Host

Every time OpenShift refers to the "default interface" on a host, it means the network interface associated with the default route. This is the logic that figures it out is here:

SDN, Overlay Network

All hosts in the OpenShift environment are clustered and are also members of the overlay network based on a Software Defined Network (SDN). Each pod gets its own IP address, by default from the 10.128.0.0/14 subnet, that is routable from any member of the SDN network. Giving each pod its own IP address means that pods can be treated like physical hosts or virtual machines in terms of port allocation, networking, naming, service discovery, load balancing, application configuration and migration.

However, it is not recommended that a pod talks to another directly by using the IP address. Instead, they should use services as an indirection layer, and interact with the service, that may be deployed on different pods at different times. Each service also gets its own own IP address from the 172.30.0.0/16 subnet.

The Cluster Network

The cluster network is the network from which pod IPs are assigned. These network blocks should be private and must not conflict with existing network blocks in your infrastructure that pods, nodes or the master may require access to. The default subnet value is 10.128.0.0/14 (10.128.0.0 - 10.131.255.255) and it cannot be arbitrarily reconfigured after deployment. The size and address range of the cluster network, as well as the host subnet size are configurable during installation. Configured with 'osm_cluster_network_cid' at installation.

The master maintains a registry of nodes in etcd, and each node gets allocated upon creation an unused subnet from the cluster network. Each node gets a /23 subnet, which means the cluster can allocate 512 subnets to nodes, and each node has 510 addresses to assign to containers running on it. Once the node is registered with the master, and gets its cluster network subnet, SDN creates on the node three devices:

- br0 - the OVS bridge device that pod containers will be attached to. The bridge is configured with a set of non-subnet specific flow rules.

- tun0 - an OVS internal port (port 2 on br0). This gets assigned the cluster subnet gateway address, and it is used for external access. The SDN configures net filter and routing rules to enable access from the cluster subnet to the external network via NAT.

- vxlan_sys_4789. This is the OVS VXLAN device (port 1 on br0) which provides access to containers on remote nodes. It is referred to as "vxlan0".

Each time a pod is started, the SDN assigns the pod a free IP address from the node's cluster subnet, attaches the host side of the pod's veth interface pair to the OVS bridge br0, adds OpenFlow rules to the OVS database to route traffic addressed to the new pod to the correct OVS port. If a ovs-multitenant plug-in is active, it also adds OpenFlow rules to tag traffic coming from the pod with the pod's VIND, and to allow traffic into the pod if the traffic's VIND matches the pod's VIND, or it is the privileged VIND 0.

Nodes update their OpenFlow rules in response to master's notification in case new nodes are added or leave. When a new subnet is added, the node adds rules on br0 so that packets with a destination IP address the remote subnet go to vxlan0 (port 1 on br0) and thus out onto the network. The ovs-subnet plug-in sends all packets across the VXLAN with VNID 0, but the ovs-multitenant plug-in uses the appropriate VNID for the source container.

The SDN does not allow the master host (which is running the OVS processes) to access the cluster network, so a master does not have access to pods via the cluster network, unless it is also running a node.

When ovs-multitenant plug-in is active, the master also allocates VXLAN VNIDs to projects. VNIDs are used to isolate the traffic.

Packet Flow

Pod IP Address

A cluster network IP address, that gets assigned to a pod.

The Services Subnet

OpenShift uses a "services subnet", also known as "kubernetes services network", in which OpenShift Services will be created within the SDN. This network block should be private and must not conflict with any existing network blocks in the infrastructure to which pods, nodes, or the master may require access to. It defaults to 172.30.0.0/16. It cannot be re-configured after deployment. If changed from the default, it must not be 172.16.0.0/16, which the docker0 network bridge uses by default, unless the docker0 network is also modified. It is configured with 'openshift_master_portal_net', 'openshift_portal_net' at installation and populates the master configuration file servicesSubnet element. Note that Docker expects its insecure registry to available on this subnet.

The services subnet IP address of a specific service can be displayed with:

oc describe service <service-name>

or

oc get svc <service-name>

The Service IP Address

An IP address from the services subnet that is associated with a service. The service IP address is reported as "Cluster IP" by:

oc get svc <service-name>

This makes sense if we think about a service as a cluster of pods that provide the service.

Example:

oc get svc logging-es NAME CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE logging-es 172.30.254.155 <none> 9200/TCP 31d

Docker Bridge Subnet

Default 172.17.0.0/16.

Network Plugin

Open vSwitch

DNS

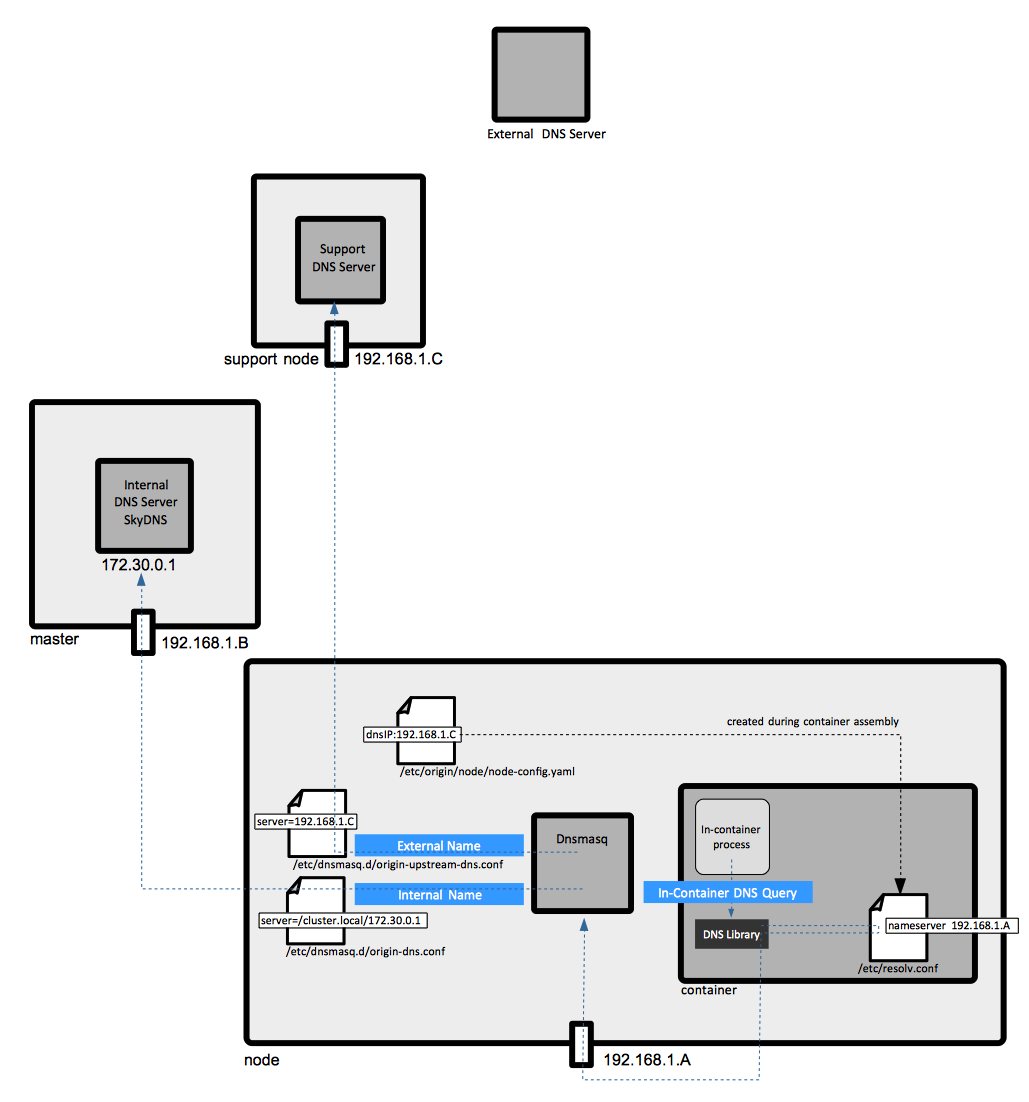

External DNS Server

An external DNS server is required to resolve the public wildcard name of the environment - and as consequence, all public names of various application access points - to the public address of the default router, as per networking workflow. If more than one router is deployed, the external DNS server should resolve the public wildcard name of the environment to the public IP address of the load balancer. For more details about initial configuration details see External DNS Setup.

Optional Support DNS Server

An optional support DNS server can be setup to translate local hostnames (such as master1.ocp36.local) to internal IP addresses allocated to the hosts running OpenShift infrastructure. There is no good reason to make these addresses and names publicly accessible. The OpenShift advanced installation procedure factors it in automatically, as long as the base host images OpenShift is installed in top of is already configured to use it to resolve DNS names via /etc/resolv.conf or NetworkManager. No additional configuration via openshift_dns_ip is necessary.

Internal DNS Server

A DNS server used to resolve local resources. The most common use is to translate service names to service addresses. The internal DNS server listens on the service IP address 172.30.0.1:53. It is a SkyDNS instance built into OpenShift. It is deployed on the master and answers the queries for services. The naming queries issued from inside containers/pods are directed to the internal DNS service by Dnsmasq instances running on each node. The process is described below.

The internal DNS server will answer queries on the ".cluster.local" domain that have the following form:

- <namespace>.cluster.local

- <service>.<namespace>.svc.cluster.local - service queries

- <name>.<namespace>.endpoints.cluster.local - endpoint queries

Service DNS can still be used and responds with multiple A records, one for each pod of the service, allowing the client to round-robin between each pod.

Dnsmasq

Dnsmasq is deployed on all nodes, including masters, as part of the installation process, and it works as a DNS proxy. It binds on the default interface, which is not necessarily the interface servicing the physical OpenShift subnet, and resolves all DNS requests. All OpenShift "internal" names - service names, for example - and all unqualified names are assumed to be in the "namespace.svc.cluster.local", "svc.cluster.local", "cluster.local" and "local" domains and forwarded to the internal DNS server. This is done by Dnsmasq, as configured from /etc/dnsmasq.d/origin-dns.conf:

server=/cluster.local/172.30.0.1

This configuration tells Dnsmasq to forward all queries for names in the "cluster.local" domain and sub-domains to the internal DNS server listening on 172.30.0.1.

This is an example of such query (where 192.168.122.17 is the IP address of the local node on which Dnsmasq binds, and 172.30.254.155 is a service IP address) :

nslookup logging-es.logging.svc.cluster.local Server: 192.168.122.17 Address: 192.168.122.17#53 Name: logging-es.logging.svc.cluster.local Address: 172.30.254.155

The non-OpenShift name requests are forwarded to the real DNS server stored in /etc/dnsmasq.d/origin-upstream-dns.conf:

server=192.168.122.12

The configuration file /etc/dnsmasq.d/origin-dns.conf is deployed at installation, while /etc/dnsmasq.d/origin-upstream-dns.conf is created dynamically every time the external DNS changes, as it is the case for example when the interface receives a new DHCP IP address.

For more details, see

Container /etc/resolv.conf

The container /etc/resolv.conf is created while the container is being assembled, based on information available in node-config.yamll. Also see:

External OpenShift DNS Resources

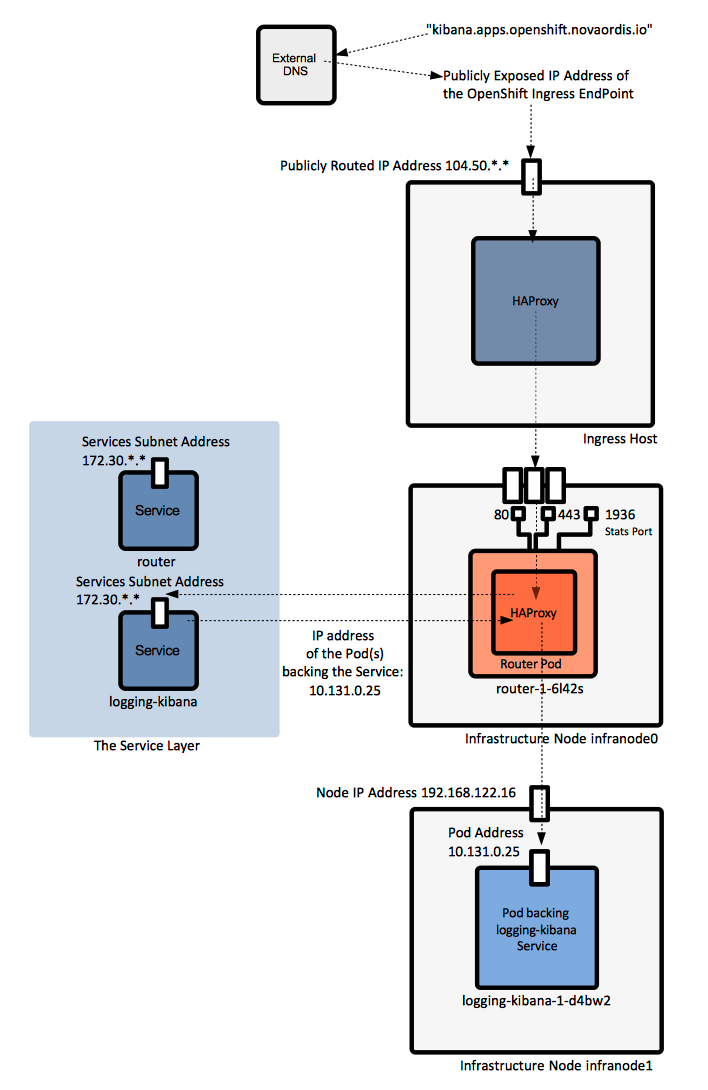

Routing Layer

OpenShift networking provides a platform-wide routing layer that directs outside traffic to the correct pods IPs and ports. The routing layer cooperates with the service layer. Routing layer components run themselves in pods. They provide automated load balancing to pods, and routing around unhealthy pods. The routing layer is pluggable and extensible. For more details about the overall OpenShift workflow, see "OpenShift Workflow".

Router

The router service routes external requests to applications inside the OpenShift environment. The router service is deployed as one or more pods. The pods associated with the router service are deployed as infrastructure containers on infrastructure nodes. A router is usually created during the installation process. Additional routers can be created with oadm router.

The router is the ingress point for all traffic flowing to backing pods implementing OpenShift Services. Routers run in containers, which may be deployed on any node (or nodes) in an OpenShift environment, as part of the "default" project. A router works by resolving fully qualified DNS external names ("kibana.apps.openshift.novaordis.io") external requests are associated with into pod IP addresses and proxying the requests directly into the pods that back the corresponding service. The router gets pod IPs from the service, and proxies the requests to pods directly, not through the Service.

Routers directly attach to port 80 and 443 on all interfaces on a host, so deployment of the corresponding containers should be restricted to the infrastructure hosts where those points are available. Statistics are usually available on port 1936.

Relationship between Service and Router

When the default router is used, the service layer is bypassed. The Service is used only to find which pods the service represents. The default router does the load balancing by proxying directly to the pod endpoints.

Sticky Sessions

The router configuration determines the sticky session implementation. The default HAProxy template implements sticky session using balance source directive.

Router Implementations

HAProxy Default Router

By default, the router process is an instance of HAProxy, referred to as the "Default Router". It uses "openshift3/OpenShift Container Platform-haproxy-router" image, and it supports unsecured, edge-terminated, re-encryption terminated and passthrough terminated routes matching on HTTP host and request path.

F5 Router

The F5 Router integrates with existing F5 Big-IP systems.

Router Operations

Information about the existing routers can be obtained with:

oadm router -o yaml

More details on router operations are available here:

Route

Logically, a route is an external DNS entry, either in a top level domain or a dynamically allocated name, that is created to point to an OpenShift service so that the service can be accessed outside the cluster. The administrator may configure one or more routers to handle those routes, typically through an Apache or HAProxy load balancer/proxy.

The route object describes a service to expose by giving it an externally reachable DNS host name.

A route is a mapping of an FQDN and path to the endpoints of a service. Each route consist of a route name, a service selector and an optional security configuration:

NAME HOST/PORT PATH SERVICES PORT TERMINATION WILDCARD logging-kibana kibana.apps.openshift.novaordis.io logging-kibana <all> reencrypt/Redirect None

A route can be unsecured or secured.

The secure routes specify the TLS termination of the route, which relies on SNI (Server Name Indication). More specifically, they can be:

- edge secured (or edge terminated). Occurs at the router, prior to proxying the traffic to the destination. The front end of the router serves the TLS certificates, so they must be configured in the route. If the certificates are not configured in the route, the default certificate of the router is used. Connection from the router into the internal network are not encrypted. This is an example of edge-termintated route.

- passthrough secured (or passthrough terminated). The encrypted traffic is send to to destination, the router does not provide TLS termination, hence no keys or certificates are required on the router. The destination will handle certificates. This method supports client certificates. This is an example of passthrough-termintated route.

- re-encryption terminated secured. This is an example of re-encyrption-termintated route.

Routes can be displayed with the following commands:

oc get all oc get routes

Routes can be created with API calls, an JSON or YAML object definition file or the oc expose service command.

Path-Based Route

A path-based route specifies a path component, allowing the same host to server multiple routes.

Route with Hostname

Routes let you associate a service with an externally reachable hostname. If the hostname is not provided, OpenShift will generate on based on the <routename>-.<namespace>].<suffix> pattern.

Default Routing Subdomain

The suffix and the default routing subdomain can be configured in the master configuration file.

Route Operations

Networking Workflow

The networking workflow is implemented at the networking layer.

- A user requests a page by pointing the browser to http://myapp.mydomain.com

- The external DNS server resolves that request to the IP address of one of the hosts that host the default router. That usually requires a wildcard C name in the DNS server pointed to the node that hosts the router container.

- Default Router selects the pod from the list of pods listed by the service and acts as a proxy for that pod (this is where the port can be translated from the external 443 to the internal 8443, for example).

Resources

- cpu, requests.cpu

- memory, requests.memory

- limits.cpu

- memory.cpu

- pods

- replicationcontrollers

- resourcequotas

- services

- Secrets

- configmaps

- persistentvolumeclaims

- openshif.io/imagestreams

Most resources can be defined in JSON or YAML files, or via an API call. Resources can be exposed via the downward API to the container.

Resource Management

Project

Projects allows groups of users to work together, define ownership of resources and manage resources - they can be seen as the central vehicle for managing regular users' access to resources. The project restricts and tracks use of resources with quotas and limits. A project is a Kubernetes namespace with additional annotations. A project can contain any number of containers of any kind, and any grouping or structure can be enforced using labels. The project is the closest concept to an application, OpenShift does not know of applications, though it provides a new-app command. A project lets a community of users to organize and manage their content in isolation from other communities. Users must be given access to projects by administrators—unless they are given permission to create projects, in which case they automatically have access to their own projects.

Most objects in the system are scoped by a namespace, with the exception of:

More details about OpenShift types are available here OpenShift types.

Each project has its own set of objects: pods, services, replication controllers, etc. The names of each resource are unique within a project. Developers may request projects to be create, but administrators control the resources allocated to the projects.

What actions a user can or cannot perform on a project's objects are specified by policies.

Constraints are quotas for each kind of object that can be limited.

New projects are created with:

oc new-project

Current Project

The current project is a concept that applies to oc, and specifies the project oc commands apply to, without to explicitly having to use the -n <project-name> qualifier. The current project can be set with oc project and read with oc status. The current project is part of the CLI tool's current context, maintained in user's .kube/config.

Global Project

In the context of an ovs-multitenant SDN plugin, a project is global if if can receive cluster network traffic from any pods, belonging to any project, and it can send traffic to any pods and services. Is the default project a global project?. A project can be made global with:

oadm pod-network make-projects-global <project-1-name> <project-2-name>

Standard Projects

Default Project

The "default" project is also referred to as "default namespace". It contains the following pods:

- the integrated docker registry pod (memory consumption based on a test installation: 280 MB)

- the registry console pod (memory consumption based on a test installation: 34 MB)

- the router pod (memory consumption based on a test installation: 140 MB)

In case the ovs-multitenant SDN plug-in is installed, the "default" project has VNID 0 and all its pods can send and receive traffic from any other pods.

The "default" project can be used to store a new project template, if the default one needs to be modified. See Template Operations - Modify the Template for New Projects.

"logging" Project

If logging support is deployed at installation or later, the participating pods (kibana, ElasticSearch, fluentd, curator) are members of the "logging" project.

This is the memory consumption based on a test installation:

- kibana pod: 95 MB

- elasticsearch pod: 1.4GB

- curator pod: 10 MB

- fluentd pods max 130 MB

"openshift-infra" Project

Contains the metrics components:

- the Hawkular Cassandra pod

- Hawkular pod

- Heapster pod

"openshift" Project

Contains standard templates and image streams. Images to use with OpenShift projects can be installed during the OpenShift installation phase, or they can be added later running command similar to:

oc -n openshift import-image jboss-eap64-openshift:1.6

Other Standard Projects

- "kube-system"

- "management-infra"

Projects and Applications

Each project may have multiple applications, and each application can be managed individually.

A new application is created with:

oc new-app

The "app" Label

TODO: app vs. application

There is no OpenShift object that represent an applications. However, the pods belonging to a specific application are grouped together in the Web console project window, under the same "Application" logical category. The grouping is done based on the "app" label value: all pods with the same "app" label value are represented as belonging to the same "application". The "app" label value can be explicitly set in the template that is used to instantiate the application with, in the "labels:" section. Some templates expose this as parameter, so it can be set on command line with a syntax similar to:

--param APPLICATION_NAME=<application-name>

Application Operations

Project Operations

Template

A template is a resource that describes a set of objects that can be parameterized and processed, so they can be created at once. The template can be processed to create anything within a project, provided that permissions exist. The template may define a set of labels to apply to every object defined in the template. A template can use preset variables or randomized values, like passwords.

Templates can be stored in, and processed from files, or they can be exposed via the OpenShift API and stored as part of the project. Users can define their own templates within their projects.

The objects define in a template collectively define a desired state. OpenShift's responsibility is to make sure that the current state matches the desired state.

Specifying parameters in a template allows all objects instantiated by the template to see consistent values for these parameters when the template is processed. The parameters can be specified explicitly, or generated automatically.

The configuration can be generated from template with oc process command.

Most templates use pre-built S2I builder images, that includes the programming language runtime and its dependencies. These builder images can also be used by themselves, without the corresponding template, for simple use cases.

New Project Template

The master provisions projects based on the template that is identified by the "projectRequestTemplate" in master-config.yaml file. If nothing is specified there, new projects will be created based on a built-in new project template that can be obtained with:

oadm create-bootstrap-project-template -o yaml

New Application Template

oc new-app <template-name>

Template Libraries

- Global template library - is this the "openshift" project?

- Project template library. A project template can be based on a JSON file and uploaded with oc create to the project library. A template stored in the library can be instantiate with oc new-app command.

- https://github.com/openshift/library

- https://github.com/jboss-openshift/application-templates

Template Operations

Build

A build is the process of transforming input parameters into a resulting object. In most cases, that means transforming source code, other images, Dockerfiles, etc. into a runnable image. A build is run inside of a privileged container and has the same restrictions normal pods have. A build usually results in an image pushed to a Docker registry, subject to post-build tests. Builds are run with the builder service account, which must have access to any secrets it needs, such as repository credentials - in addition to the builder service account having to have access to the build secrets, the build configuration must contain the required build secret. Builds can be triggered manually or automatically.

OpenShift supports several types of builds. The type of build is also referred to as the build strategy:

Builds for a project can be reviewed by navigating with the web console to the project -> Builds -> Builds or invoking oc get builds from command line. Note these are actual executed builds, not build configurations.

Build Strategy

Docker Build

Docker can be used to build images directly. The Docker build expects a repository with Dockerfile and all artifacts required to produce runnable image. It invokes the docker build command, and the result is a runnable image.

Source-to-Image (S2I) Build

A source to image build strategy is a process that takes a base image, called the builder image, application source code and S2I scripts, compiles the source and injects the build artifacts into the builder image, producing a ready-to-run new Docker image, which is the end product of the build. The image is then pushed into the integrated Docker registry.

The essential characteristic of the source build is that the builder image provides both the build environment and the runtime image in which the build artifact is supposed to run in. The build logic is encapsulated within the S2I scripts. The S2I scripts usually come with builder image, but they can also be overridden by scripts placed in the source code or in different location, specified in the build configuration. OpenShift supports a wide variety of languages and base images: Java, PHP, Ruby, Python, Node.js. Incremental builds are supported. With a source build, the assemble process performs a large number of complex operations without creating a new layer at each step, resulting in a compact final image.

The source strategy is specified in the build configuration as follows:

kind: BuildConfig

spec:

strategy:

type: Source

sourceStrategy:

from:

kind: ImageStreamTag

name: jboss-eap70-openshift:1.5

namespace: openshift

source:

type: Git

git:

uri: ...

output:

to:

kind: ImageStreamTag

name: <app-image-repository-name>:latest

The builder image is specified with a 'spec.strategy.sourceStrategy.from' element. Source code origin is specified with 'spec.strategy.source' element. Assuming that the build is successful, the resulted image is pushed into the ? image stream and tagged with the 'output' image stream tag.

A working S2I Build Example is available here:

An example to create a source build configuration from scratch is available here:

The Build Process

For a source build, the build process takes place in the builder image container. It consists in the following steps:

- Download the S2I scripts.

- If it is an incremental build, save the previous build's artifacts with save-artifacts.

- A work directory is created.

- Pull the source code from the repository into the work directory.

- Heuristics is applied to detect how to build the code.

- Create a TAR that contains S2I scripts and source code.

- Untar S2I scripts, sources and artifacts.

- Invoke the assemble script.

- The build process changes to 'contextDir' - anything that resides outside 'contextDir' is ignored by the build.

- Run build.

- Push image to docker-registry.default.svc:5000/<project-name>/...

Builder Image

The builder image is an image that must contain both compile time dependencies and build tools, because the build process take place inside it, and runtime dependencies and the application runtime, because the image will be used to create containers that execute the application. The builder image must also contain the tar archiving utility, available in $PATH, which is used during the build process to extract source code and S2I scripts, and the /bin/sh command line interpreter. A builder image should be able to generate some usage information by running the image with docker run. An article that shows how to create builder images is available here: https://blog.openshift.com/create-s2i-builder-image/.

Extended Build

An extended build uses a builder image and a runtime image as two separate images. In this case the builder image contains the build tooling but not the application runtime. The runtime image contains the application runtime. This is useful when we don't want the build tooling laying around in the runtime image.

S2I Scripts

The S2I scripts encapsulate the build logic and must be executable inside the builder image. They must be provided as an input of the source build and play an essential role in the build process. They come from one of the following locations, listed below in the inverse order of their precedence (if the same script is available in more than one location, the script from the location listed last in the list is used):

- Bundled with the builder image, in a location specified as "io.openshift.s2i.scripts-url" label. A common value is "image:///usr/local/s2i". As an example, these are the S2I scripts that come with an EAP7 builder image: assemble, run and save-artifacts.

- Bundled with the source code in an .s2i/bin directory of the application source repository.

- Published at an URL that is specified in the build configuration definition.

Both the "io.openshift.s2i.scripts-url" label value specified in the image and the script specified in the build configuration can take one of the following forms:

- image:///<path-to-script-directory> - the absolute path inside the image.

- file:///<path-to-script-directory> - relative or absolute path to a directory on the host where the scripts are located.

- http(s)://<path-to-script-directory> - URL to a directory where the scripts are located.

The scripts are:

assemble

This is a required script. It builds the application artifacts from source and places them into appropriate directories inside the image. The script's main responsibility is to turn source code into a runnable application. It can also be used to inject configuration into the system.

It should execute the following sequence:

- Restore build artifacts, if the build is incremental. In this case save-artifacts must be also defined.

- Place the application source in the build location.

- Build.

- Install the artifacts into locations that are appropriate for them to run.

EAP7 builder image example: assemble.

run

This is a required script. It is invoked when the container is instantiated to execute the application.

EAP7 builder image example: run.

save-artifacts

This is an optional script, needed when incremental builds are enabled. It gathers all dependencies that can speed up the build process, from the build image that has just completed the successful build (the Maven .m2 directory, for example). The dependencies are assembled into a tar file and streamed to standard output.

EAP7 builder image example: save-artifacts.

usage

This is an optional script. Informs the user how to properly use the image.

test/run

This is an optional script. Allows to create a simple process to check whether the image is working correctly. For more details see:

Incremental Build

The source build may be configured as an incremental build, which re-uses the previously downloaded dependencies and previously built artifacts, in order to speed up the build. Incremental builds reuse previously downloaded dependencies, previously built artifacts, etc.

strategy

type: "Source"

sourceStrategy:

from:

...

incremental: true

Webhooks

A source build can be configured to be automatically trigged when a new event - most commonly a push - is detected by the source repository. When the repository identifies a push, or any other kind of event it was configured for, it makes a HTTP invocation into an OpenShift URL. For internal repositories that run within the OpenShift cluster, such as Gogs, the URL is https://openshift.default.svc.cluster.local/oapi/v1/namespaces/<project-name>/buildconfigs/<build-configuration-name>/webhooks/<generic-secret-value>/generic. The secret value can be manually configured in the build configuration, as shown here, but it is usually set to a randomly generated value when the build configuration is created. For an external URL, such as GitHub, the URL must be publicly accessible TODO. Once the build is triggered, it proceed as it would otherwise proceed if it was triggered by other means. Note that no build server is required for this mechanism to work, though a build server such as Jenkins can be integrated and configured to drive a pipeline build.

The detailed procedure to configure a webhook trigger is available here:

Tagging the Build Artifact

Once the build process (the assemble script) completes successfully, the build runtime sets the image's command to the run script, and tags the image with the output name specified in the build configuration.

TODO. How to tag the output image with a dynamic tag that is generated from the information in the source code itself?

MAVEN_MIRROR_URL

TODO 'MAVEN_MIRROR_URL' is an environment variable interpreted by the s2i builder, which use the Maven repository whose URL is specified as a source of artifacts. For more details see:

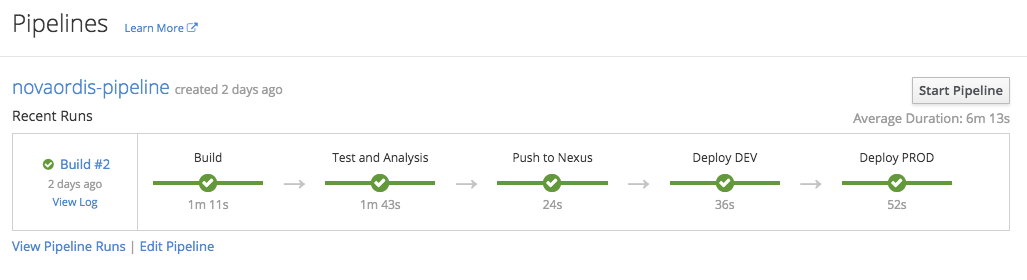

Pipeline Build

The pipeline build strategy allows the developers to defined the build logic externally, as a Jenkins Pipeline. The logic is executed by an OpenShift-integrated Jenkins instance, which uses a series of specialized plug-ins to work with OpenShift. More details about how OpenShift and Jenkins interact are available in the OpenShift CI/CD Concepts page. The specification of the build logic can be embedded directly into an OpenShift build configuration object, as shown below, or it can be specified externally into a Jenkinsfile which is then later automatically integrated with OpenShift. The build can then be started, monitored, and managed by OpenShift in the same way as any other build type, but it can at the same time be managed from the Jenkins UI - these two representations are kept in sync. The pipeline's graphical representation is available both in the integrated Jenkins instance and it OpenShift directly, as a "Pipeline":

The pipeline build strategy is specified in the build configuration as follows:

kind: BuildConfig

spec:

strategy:

type: JenkinsPipeline

jenkinsPipelineStrategy:

jenkinsfile: |-

node('mvn') {

//

// Groovy script that defines the pipeline

//

}

source:

type: none

output: {}

This is an example of specifying the build logic inline in the build configuration. It is also possible to specify the build logic externally in a Jenkinsfile. Note that unlike in the source build's case, no "output" are specified, because this is fully defined in the Jenkins Groovy script. "source" may be used to specify a source repository URL that contains the Jenkinsfile pipeline definition.

An example of how to create a pipeline build configuration from scratch is available here:

CI/CD

OpenShift enables DevOps. It has built-in support for the Jenkins CI server, providing a native way of doing CI/CD.

Custom Build

The custom build strategy allows to define a specific builder image responsible for the entire build process, which allows you to customize the build process.

The custom builder image is a plain Docker image embedded with build process logic.

Chained Builds

Two builds may be chained: one produces binaries from a builder image and source, and pushes the artifacts into an image stream; the other pulls the binaries produces by the first build from the image stream and places them into a runtime image, based on a Dockerfile, A separated image is thus created.

Build Configuration

A BuildConfig object is the definition of an entire build. It contains a description of how to combine source code and a base image to produce a new image. The BuildConfig lists the location of the source code, the build triggers, the build strategy, various other build configuration parameters, such as maximum allowed duration, and the specification of the output of the build, which is in most cases a Docker container that gets pushed into the integrated registry. Both oc new-app and oc new-build create BuildConfig objects. The preferred way to create a build configuration is to start with oc new-build and customize the resulted build configuration:

Generally, immediately after the build configuration is declared, a build starts, and if it successful, a new image will be pushed into the artifact image stream.

Build Trigger

Builds can be triggered by the following events:

TODO: when does a build start automatically and when doesn't.

github, generic, gitlab, bitbucket

Source code change signaled by a GitHub webhook or a generic webhook. An internal repository repository must be configured to invoke into an URL similar to https://openshift.default.svc.cluster.local/oapi/v1/namespaces/$CICD_PROJECT/buildconfigs/<application-name>/webhooks/${WEBHOOK_SECRET}/generic. An external repository must be configured to invoke either into Jenkins using a URL similar to ? or into the associated build configuration, using an URL similar to ?.

ImageChange

Base image change, in case of source-to-image builds.

Build Configuration Change

Manual Build

Manual with oc start-build.

Build Source

A build configuration accepts the following type of sources:

- Git

- Binary (Git and binary are mutually exclusive). See https://docs.openshift.com/container-platform/latest/dev_guide/builds/build_inputs.html#binary-source.

- Dockerfile

- Image

- Input secrets

- External artifacts

Build Secrets

The source element may refer to build secrets:

kind: BuildConfig

...

spec:

...

source:

...

sourceSecret:

name: some-secret

Build Node Selection

Build can be assigned to specific nodes, by specifying labels in the "nodeSelector" field of the build configuration:

kind: BuildConfig

...

spec:

nodeSelector:

env: app

Build Resources

Can be setup in the build configuration:

kind: BuildConfig

spec:

resources:

limits:

cpu: ...

memory: ...

Build Operations

Image

An OpenShift image represents a immutable container image in Docker format. Images are not project-scoped, but cluster-scoped: any user from any project can get information about any image in the cluster with oc get images, provided that it has sufficient cluster-level privileges. One role that permits inspecting image information is /cluster-reader . On the other hand, a user that only has project-level privileges cannot inspect images.

Information about a specific image can be obtained with oc get image <image-name>

Image Name

An image is identified by a name, which is the SHA256 hash of the image: "sha256:ea573da7c263e68f2d021c63bec218b79699a0b48e58b3724360de9c6900ca46". The name can be local to the current cluster - the images produced as artifacts of the cluster's project do not exist anywhere else, until they are explicitly published - or point to a remote Docker registry. An OpenShift cluster usually comes with its own integrated Docker registry, accessible to all projects, whose main function is to store images produced by the projects as result of build activities.

Image Reference

The image contains a "dockerImageReference" entry that maintains the location the image can be found at:

docker-registry.default.svc:5000/novaordis-dev/tasks@sha256:41976593d219eb2008a533e7f6fbb17e1fc3391065e2d592cc0b05defe5d5562

registry.access.redhat.com/redhat-openjdk-18/openjdk18-openshift@sha256:ea573da7c263e68f2d021c63bec218b79699a0b48e58b3724360de9c6900ca46

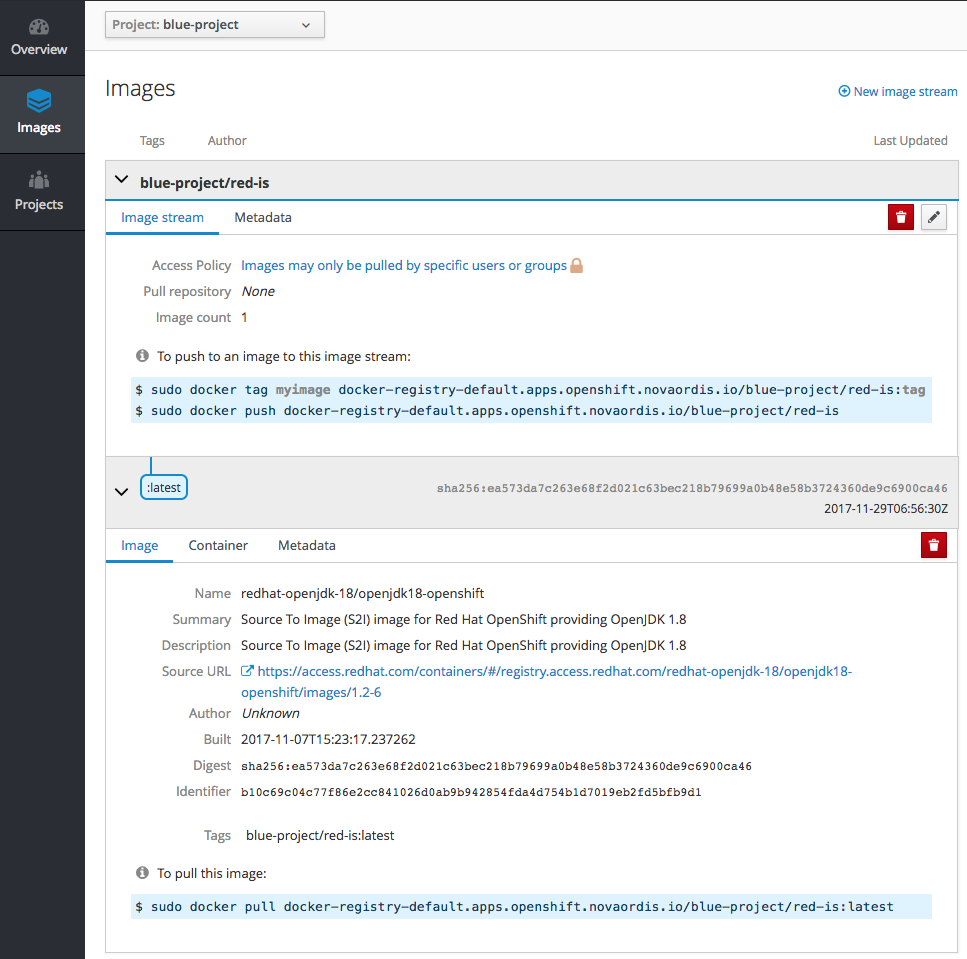

Image Stream

An image stream is similar to a Docker image repository, in that it contains a group of related Docker images identified by image stream tags. Logically it is analogous to a branch in a source code repository. The image stream presents a single virtual view of related images and allow you to control which images are rolled out to your builds and applications. The stream may contain images from the OpenShift integrated Docker registry, other image streams, other image repositories. OpenShift stores complete metadata about each image, including example command, entry point and environment variables.

Image streams exist as OpenShift objects, describable with oc get is, but they also have a representation in the cluster's integrated docker repository docker-registry.default.svc:5000/, as project-name/image-stream-name. As an example, for a "blue-project" and a "red-is":

kind: ImageStream

metadata:

...

name: red-is

namespace: blue-project

spec:

tags:

- name: latest

from:

kind: DockerImage

name: registry.access.redhat.com/redhat-openjdk-18/openjdk18-openshift

Example of a JSON file that can be used to create image streams in OpenShift:

Builds and deployments can watch an image stream to receive notifications when new images are added and react by performing a build or a deployment.

Operations:

"openshift" Image Streams

A set of standard image streams come pre-configured in the "openshift" project of an OpenShift installation, but image streams can be created in any project.

Image Stream Lookup Policy

The lookup policy specifies how other resources reference this image within this namespace.

Possible values:

- local - will change the docker short image reference, such as "mysql" or "php:latest" on objects in this namespace to the image ID whenever they match this image stream, instead of reaching out to a remote registry. The name will be fully qualified to an image ID if found. The gag's referencePolicy is taken into account on the replaced value. It only works within the current namespace.

Image Stream Tag

The default tag is called "latest". A tag may point to an external Docker registry, at other tags in the same image stream, a different image stream, or be controlled to directly point to known images. An image stream tag full name is <image-stream-name>:<tag-name>. For example, the tag "0.11.29" exposed by the "gogs" image stream as shown here:

...

kind: ImageStream

metadata:

name: gogs

spec:

tags:

- name: "0.11.29"

...

is referred to by a deployment configuration as:

...

triggers:

- type: ImageChange

imageChangeParams:

...

from:

kind: ImageStreamTag

name: gogs:0.11.29

Images can be pushed to an image stream tag directly via the integrated Docker registry.

The image stream tag has a referencePolicy, which defines how other components should consume this image. The reference policy's type determines how the image pull spec should be transformed when the image stream tag is used in deployment configuration triggers or new builds. The default value is "Source", indicating the original location of the image should be used (if imported). The user may also specify "Local", indicating that the pull spec should point to the integrated Docker registry and leverage the registry's ability to proxy the pull to an upstream registry. "Local" allows the credentials used to pull this image to be managed from the image stream's namespace, so others on the platform can access a remote image but have no access to the remote secret. It also allows the image layers to be mirrored into the local registry which the images can still be pulled even if the upstream registry is unavailable.

Image Pull Policy

When the container is created, the runtime uses the "imagePullPolicy" to determine whether to pull the image prior to starting the container. More details available here:

Deployment

A deployment is a replication controller based on a user-defined template called a deployment configuration: a successful deployment results in a new replication controller being created.

A deployment adds extended support for software development and deployment lifecycle. Deployments are created manually or in response to triggered events, and the most common events that trigger a deployment are either an image change or a configuration change.

The deployment system provides a deployment configuration, which is a template for deployments, triggers that drive automated deployments in response to events, user-customizable strategies to transition from the previous deployment to the new deployment, rollback procedure, and manual replication scaling. Deployment configuration version increments each time new deployment is created from configuration. Deployments allow defining hooks to be run before and after the replication controller is created.

Deployments allow rollbacks.

Deployments allow manual replication scaling or autoscaling.

The deployments are triggered with oc deploy.

Deployment Configuration

A deployment configuration is a user-defined template for performing deployments, which result in running applications. The deployment configuration defines the template for a pod. It manages deploying new images or configuration changes whenever those change. A single deployment configuration is usually analogous to a single micro service.

Each deployment is represented as a replication controller. The OpenShift environment creates a replication controller to run the application in response to a deployment configuration. The deployment configuration contains a version number that is incremented each time a replication controller is created from the configuration.

Deployment configurations can support many different deployment patterns, including full restart, customizable rolling updates, and fully custom behaviors, as well as pre- and post-hooks. It supports automatic rolling back to the last successful revision of configuration, in case the current template fails to deploy.

The DeploymentConfig contains:

- Replication controller definition.

- Default replica count fo the deployment.

- Triggers for creating new deployments automatically, in response to events. If no triggers are defined, deployments must be started manually.

- Strategy for transitioning before deployments.

- Life-cycle hooks. Every hook has a failure policy (Abort, Retry, Ignore).

The DeploymentConfig for a project can be listed with:

oc get all oc get dc

Deployment Triggers

The deployment triggers are specified in the deployment configuration, and can be modified from command line:

ConfigChange

Results in a new deployment, and a new replication controller being created whenever changes are detected to replication controller template of deployment configuration. In the presence of a ConfigChange trigger, the first replication controller is automatically created when the deployment configuration itself is created.

ImageChange

The deployment trigger is a change in the image stream. If we do not want the result of a build to be deployed automatically, even if the build pushes a new image in the repository, we simply do not list the "ImageChange" deployment trigger in the deployment configuration.

Replication Controller